The Curse of Being a “Gifted” Child

We celebrate “gifted” children at a young age, but what happens to them when they grow up?

By Mekhala Mira

August 25, 2025

In high school, I was voted as "Best Singer" by my classmates in our senior yearbook. It felt like a natural conclusion. It was obvious. I was the best — because I'd been told I was the best since childhood. I was born with a "gift."

Over the next few years, I got jaw surgery to fix an underbite, two gum and bone grafts, and two teeth implants — on top of the braces I already had. I had never had to work hard to sing before. I thought everything would be the same. But it wasn't.

I developed a condition called Muscle Tension Dysphonia (MTD), a vocal disorder where excessive muscle tension around the larynx causes hoarseness, pitch instability, and pain in the throat when singing. Suddenly, my throat burned when I sang, I was coughing when I tried to sing notes that had been easy, and I couldn't sing more than one song without my voice breaking like a 13-year-old boy going through puberty. It was devastating.

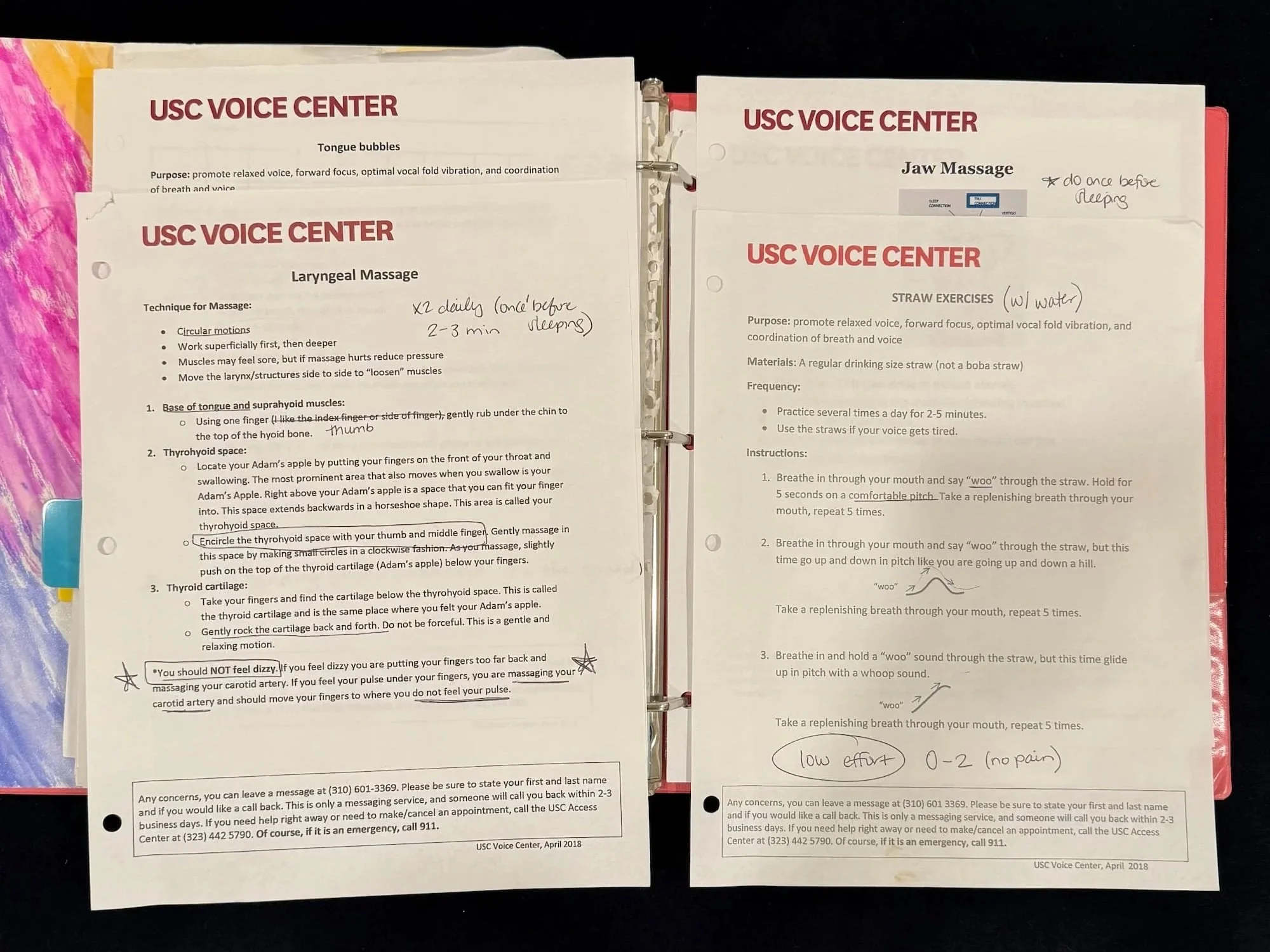

I tried everything to "fix" my voice. I went through physical therapy, saw several different voice and speech therapists, took voice lessons with numerous teachers, and even got a frenulectomy on my tongue, but ultimately, nothing would change — because I simply could not motivate myself to put in the effort to make meaningful change. I blamed myself, heaping the judgments of "lazy," "spoiled," and "unworthy" onto my psyche, which made it even more difficult to cope with a lack of results. After doing some research, I learned that being labeled as "gifted" at a young age can cause these patterns to develop.

Vocal therapy exercises (that I didn’t do)Studies have shown that children who are praised for their performance suffer a decrease in enjoyment, persistence, and achievement than children who are praised for their effort. Performance-praised children are risk averse — they often choose "safe" tasks that ensure a good performance so they’ll never have to face failure. Failure for someone who is performance-praised leads to a loss of motivation, whereas failure for someone who is effort-praised leads to persistence.

It makes sense. If you've never been praised in the face of a setback, then mistakes are seen as something to avoid, and if mistakes must be avoided, then you must run from challenges that threaten your success. But that course of action is a death sentence for your potential. Your instinct will always be to tell yourself you’re not capable of something before you even try. It takes an extraordinary amount of energy to fight through that mental barrier as an adult.

I only enjoy singing in my daydreams now. I don't feel motivated to improve. It's hard for me to even listen to songs I used to love singing. For someone who was a "gifted" singer as a child, facing failure after failure with my voice sucked the enthusiasm and drive out of me, just like it has with so many other "gifted" children.

Singing at my high school graduation ceremony, age 18My vocal cord exam, where I was diagnosed with Muscle Tension Dysphonia, age 23

One could argue that parents are motivating their children to work hard by praising positive results. That's probably what my parents would have said. But that argument misses a key point. Research shows that performance-praise can lead to hard work and success, but it only lasts for as long as that success is sustained. Once performance-praised children face inevitable setbacks, they lose the motivation, enjoyment, and achievement that effort-praised children would find in the face of failure.

I got numerous public opportunities to sing when I was younger, but once I lost my "gifted" voice, my inclination was to give up instead of adapting to my new circumstances. If my parents had shown interest in my progress in voice lessons instead of just my final performances, I may have been better equipped to face the loss of my voice with resilience instead of hopelessness. I'd probably have long-since released the EP I've been holding onto for 4 years. I'd probably be performing every weekend instead of only once in the last 6 years.

I don't hold resentment towards my parents though. They did the best they could with what they knew. It makes sense that parents want their children to excel in a visible way. After all, our society rewards people for proof of their abilities, not for proof of their progress. For example, artists are always evaluated on their performances. Actors are told, "Your performance was amazing," or "You deserve an Oscar," but they rarely hear, "I'm impressed with the work you put into developing your character." Singers are told, "You sounded amazing," or only their highest belted note is cheered, but you rarely hear, "The effort you put into expanding your range is impressive." The message: "You don't deserve to be recognized unless others think you're special.”

The “Best Singer” award page in my high school yearbookBut even though that's what it appears society values, those visibly successful people you see as uniquely gifted did not get there because they were performance-praised — they got there in spite of being performance-praised. You don't find that level of success without facing a multitude of failures. If they succeeded in the face of those failures, it's because they were able to sustain their work ethic and enjoyment for their craft through their struggles. Their efforts were clearly praised along the way by those closest to them. It may seem counterintuitive, but if you truly want your child to succeed, you must encourage them to fail, because in encouraging them to fail, you're actually encouraging them to try.

Mekhala Mira is a writer, producer, and musician based in Los Angeles, California. Her work, rooted in both research and radical vulnerability, examines how the world around us shapes our internal lives.

I know - just hear me out.

“AI-generated art is the future,” is a narrative that has dominated our public discourse, but it ignores the reality of why we’re drawn to art in the first place.